In the early 1900s, Atlanta’s residential development was exploding in the “streetcar suburbs” that had begun developing around the city in the 1890s. For the city’s wealthy white population, development of Ansley Park in 1904 and Druid Hills in 1909 continued and expanded on the concept of the garden suburb that was attempted by Joel Hurt in Inman Park in 1889. But with the rapid expansion of automobile use in the years leading up to World War I, developers were no longer tied to the streetcar lines and could begin catering to those for whom automobiles made possible real escape from the confines of the city. Construction of Spotswood Hall dates to this early pre-war period when the development of the residential area now generally known as Buckhead was only just beginning.

|

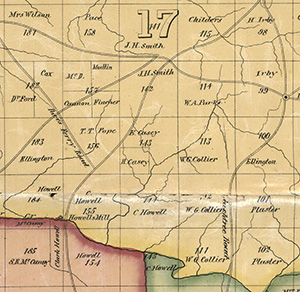

Figure 1. Detail from Pittman's map of Fulton County, 1872, with the future site of Spotswood Hall in Land Lot 143 at center. Irbyville, later known as Buckhead, is at upper right. Peachtree Creek meanders across the bottom of this image. (Atlanta-Fulton County Public Library)

|

|

Figure 2. Robert F. Maddox's Woodhaven, built in 1911, the first of the great Buckhead estates. (Atlanta History Center) |

By the end of the nineteenth century, the old-timers who had settled the area in the 1820s and 1830s were beginning to die, and in most cases, their children and grandchildren were more than willing to profit from the tremendous growth of Atlanta and the increasing demand for suburban development. Speculation in real estate grew as the area transitioned from farmland to suburb, as in November 1903 when James L. Dickey (1875–1968) paid F. M. Powers $6,000 for four hundred acres in Land Lots 141 and 142 and then sold Mayor Robert Foster Maddox (1870–1965) seventy-three acres in Land Lot 141 for $6,578 in May 1904.

Just as the death of George W. Collier in 1903 had precipitated the development of Ansley Park, so the death of his brother Wesley Gray Collier in 1906 set the stage for tremendous development north of Peachtree Creek. In May 1910, the executors of Collier's estate, Eretus Rivers and Walter P. Andrews (1865–1935), sold Collier’s old farm to the Peachtree Heights Park Company. The sale included 500 acres in three land lots, including over 3,000 feet of frontage along Peachtree Road north of Peachtree Creek. On the west, the old Howell Mill Road meandered in a northeasterly direction, and Peachtree Battle Avenue and Wesley Road, which bounded the development on the south and the north respectively, were already under construction. The Peachtree Heights Park Company hired the New York architectural firm of Carrère and Hastings to lay out the subdivision and, by the spring of 1911, work was underway to create Habersham Road from Peachtree Battle Avenue to Pace’s Ferry Road.

That same year, 1911, Mayor Maddox built Woodhaven, the first of the great country estates along Pace’s Ferry Road. The Tuxedo Park Company also acquired three hundred acres of the old Dickey estate along Pace’s Ferry Road to begin their own residential development. “Already,” the Atlanta Journal noted in reporting the first auction of lots in May 1911, “the colony along Pace’s Ferry Road is accorded first place in suburban development in Atlanta.” Incorporated into the city in 1954, W. Pace’s Ferry Road and adjacent streets remain among the city’s most prestigious addresses. [1]

Land Lot 143

In January 1913, intent on capitalizing on the development of Peachtree Heights Park and Tuxedo Park, the North Highland Investment Company, through one J. B. Lowry of Hamilton County, Tennessee, purchased an option on 97.37 acres in the north half of Land Lot 143, 17th District, from Mrs. Maria L. Dolphyn (1844–1932) in January 1913. An Oklahoma resident, Mrs. Dolphyn was born in Massachusetts and married an Englishman, William L. Dolphyn (1849–1917), in 1872. She had owned the property since the early 1900s, but under what circumstances she acquired it in the first place has not been established.

Hiram Casey (1800–1874) was one of the first white settlers in the area, acquiring Land Lot 143 in the 1830s and raising a large family there in the 1840s and 1850s. His son Elisha Casey (1829–1917) inherited the northern half of the land lot after Hiram’s death in 1874 and may have lived not far from the future site of Spotswood Hall.

Dolphyn’s sale of the property for $34,000 was another example of the rapid increase in property values that attended the new suburban developments in the area. The contract laid out a series of payments to be completed by January 1917 but, as lots were sold in the meantime, Mrs. Dolphyn agreed to transfer title to the company for $350 per acre. As was the case with much of Atlanta’s early twentieth century residential development, the property was sold “with the restriction that no part of the same shall be sold to persons of color within sixty (60) years from this date.”[2]

Until 1913, the only road through Land Lot 143 crossed the northwest corner of the lot. Running between Roswell Road and the Peachtree Creek bridge at Howell Mill, it had evolved out of ancient Indian trails that generally followed the routes of what are now Dover Road, Arden Road, and the northern segment of Habersham Road. In order to subdivide the property, a new road was laid out that curved to the west from the newly extended Habersham Road and, following the natural contours of the land, wrapped the south face of the prominent hill top in the northwest side of LL 143 before ending at the existing road on the west.

The new road was first christened Peachtree Heights Road, but was renamed Argonne Drive in the 1920s to commemorate the site of some of the deadliest battles in World War I. The old road from Howell Mill to Roswell was also re-christened, first as Hemphill Road, in honor of the ex-mayor, but soon renamed Arden Road for the home that James L. Dickey Jr. (1875–1968) built near the road’s intersection with Pace’s Ferry Road in 1917. Even though the North Highland Company’s tract was not a formal part of the Peachtree Heights development, the Company’s plans for development of the north half of LL 143 were meant to complement and expand what was begun in Peachtree Heights Park.

|

Figure 3. Detail from the city's 1927 topographical survey, annotated with an arrow to locate Spotswood Hall. (Pullen Library, Georgia State University) |

Shelby Smith (1871–1943)

One of the ten investors in the North Highland Investment Company was Shelby Smith Sr., the son of Charles and Mary Smith, who was born on the family farm in Catoosa County in northwest Georgia just as Reconstruction was running its course. Details of his youth are few, but he married Nell Littlefield in 1890 and, apparently unwilling to continue his father's farm, they moved to Chattanooga where he began his business career. Their first child was born in 1892, and, two years later, they moved to Atlanta.

The nation was in the middle of a severe economic downtown that lasted most of the decade, but Smith was soon working as an advertising agent for the Atlanta Journal and the Atlanta Constitution. Although he continued that work for some twelve years, by 1900, he was already developing his own real estate business, which "eventually grew to very appreciable volume and importance." By then, too, the Smiths were living on Woodward Avenue in southeast Atlanta and had five children, born at regular intervals throughout the preceding decade.[3]

|

Figure 4. View of the Fulton County Courthouse (1911-1913), designed by A. Ten Eyck Brown and built during Shelby Smith's tenure on the county commission. (National Register of Historic Places) |

In 1911, Smith began the first of two terms on the Fulton County Board of Commissioners, serving as its chairman in 1913. In his first year in office, he was among those who selected a design by A. Ten Eyck Brown (1878–1940) for a new courthouse, which was completed in 1914. That same year, Smith incorporated a company that specialized in heavy, road-building equipment and profited greatly from the enormous demand as the “Good Roads” movement gathered steam in the 1910s. Among those roads was Northside Drive, which was built along the west line of Land Lot 143 in the 1920s.

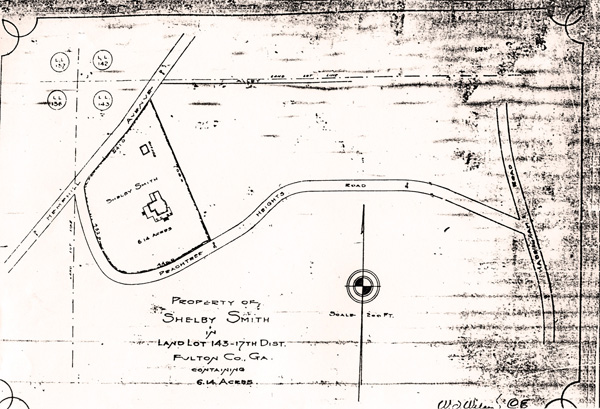

In November 1913, Smith paid the North Highland Investment Company $4,000 for a 6.14 acre parcel that encompassed the entire hill top on the north side of Peachtree Heights Road (now Argonne Drive) at Hemphill Road (now Arden Road). With little of the tree cover that now characterizes the area, there was a magnificent view of the city to the south across the valley of Peachtree Creek, making the site one of the most prominent locations in the entire area. Few details of the house’s construction can be documented. Being outside the city limits, there was no building permit but, in December 1913, W. J. Wilson completed a plat of Smith’s property which showed the footprint of the house and that of a garage in the rear, suggesting that the house had already been built. When the information for the 1915 city directory was compiled in the fall of 1914, Shelby Smith gave his address simply as Peachtree Heights Road. It is assumed that the house was completed by the end of 1913. [4]

Figure 5. Wilson's plat of Shelby Smith's property dated December 1913. (Fulton County Plat Book 6-46) |

The house’s Neo-Classical design has been attributed to A. Ten Eyck Brown (1878-1940), one of the city’s best-known architects in the early twentieth century. With Morgan & Dillon, Brown designed the Fulton County Courthouse, which had been in the planning stages since 1907, although work did not get underway until 1911, just as Smith was beginning his service on the county commission. Unfortunately, the house does not appear in either of Brown’s two lists of projects (1913 and 1924), although neither of them claimed to be all-inclusive. Smith served on the building committee for construction of the new courthouse and would certainly have been acquainted with Brown. Smith’s daughter believed that the house her father built in 1913 was the work of Brown and, barring new evidence, her word might be accepted as fact.

Featuring a facade dominated by a full-height pedimented porch supported by elaborated Ionic columns, Smith’s house was an excellent example of early twentieth century Neo-Classical architecture. The architecture of Chicago’s World Columbian Exposition in 1893 had sparked a renewed interest in Classical design of all sorts and, by 1895, an eclectic Neo-Classical Revival style had developed out of earlier Georgian, Adam, Early Classical Revival and Greek Revival precedents. Although never as popular as the Colonial Revival, Neo-Classical architecture enjoyed great popularity in the years before World War I and, in a second phase of development, the style continued to be used until the middle of the twentieth century. Some of these houses were masonry, a notable example being Asa Candler’s “Callan Castle” (1903) in Inman Park but wood-framed examples were more typical. The Zuber-Jarrell House (1905) on Flat Shoals Road in southeast Atlanta is another excellent wood-framed example of the style and is particularly interesting in that its floor plan and many of its architectural details are almost identical to those of the original Spotswood Hall.

Development of Peachtree Heights and adjacent areas was slowed by the outbreak of World War I and, throughout the war years, Smith’s house remained relatively isolated. He retired from the Fulton County Commission in 1914 but continued his career as a real estate developer and road builder. He worked “from Florida to Tennessee,” according to his daughter, with some of his work taking him out of the city for a year or more at the time. Described as a “wheeler-dealer” by one descendant, Smith sold the house and its 6.4 acre lot in 1918 and moved to a new house on Wesley Road where he resided until 1921. He later moved to Druid Hills, where he was living when he died in April 1943. He is buried at Westview Cemetery in Atlanta.

|

Figure 6. Spotswood Hall in 1929 before the large changes in 1933. (Photograph from Hornaday's book Georgia Homes and Landmarks) |

Lucian Lamar Knight (1868–1933)

The new owner of the house was Lucian Lamar Knight, a noted newspaper editor and historian whom Smith probably already knew from his own newspaper days. Born in Atlanta, Knight lost his father, George Walton Knight, before he was two years old. Lucian and his sister Mary were raised by their widowed mother, with the assistance of her older brother John Benning Daniel, who lived with them part of the time. [5]

Lucian graduated from the University of Georgia in 1888 and went on to law school, receiving his degree in an accelerated program of study in 1889. He practiced law in Macon, Georgia, before moving to Atlanta in 1890. Two years later, he started ten years at the Atlanta Constitution working as a popular reporter and editor. During this period began his life-long interest in state and local history.

In 1902 he resigned from the paper to study theology at Princeton and was ordained a minister in the Presbyterian Church in 1905. Unfortunately, his ten-year marriage to Edith Nelson was beginning to unravel by that time and, on the verge of a nervous breakdown, Knight went to Europe in early 1906. By the end of the year he had moved to California, where he joined a Los Angeles law firm. While there, he lived on Catalina Island and compiled the first of several major works on Georgia’s history, Reminiscences of Famous Georgians. Published in 1907 and followed by a second volume in 1908, these books established a direction for the rest of Knight’s life.

Figure 7. Undated photograph of Lucian Lamar Knigiht. (New Georgia Encyclopedia) |

He returned to Atlanta in 1908 where he lived with his uncle John Daniel and his widowed aunt Mattie Shepherd on N. Jackson Street. He and his wife at last divorced in 1909. He worked as managing editor for a publishing company and as associate editor for the Atlanta Georgian. In 1913, Knight succeeded former governor William Northen as compiler of state records and, over the next five years, saw publication of four volumes of the state’s Colonial Records; Georgia’s Landmarks, Memorials, and Legends in two volumes; and six volumes of A Standard History of Georgia and Georgians.

In 1917, Knight married Rosa Talbot Reid, who shared his interest in history. The next year, the Georgia Legislature created the Department of Archives and History and appointed Knight as its first director. In November 1918, the Knights bought the old Smith house, which was rechristened “Spotswood Hall,” commemorating one of Knight’s ancestral homes in Virginia.

Knight had the misfortune to spend the first part of his tenure as director of the new department in fending off the first of what would be several efforts over the years to abolish the Department of Archives and History entirely. But with his wife’s assistance, he was able to bring some semblance of order to the state’s records, and by the time that he retired from the department in 1925, the State had a “secure and permanent archives.”

In the 1920s, Peachtree Heights Road was renamed Argonne Drive, in memory of one of the greatest battles of World War I, giving Spotswood Hall a new address: 555 Argonne Drive. Other houses were being built along the street, but the area, especially to the west and northwest, remained largely undeveloped. Spotswood Hall was featured in Annie Hornady Howard’s Georgia Homes and Landmarks in 1929, just as Knight’s comfortable retirement was about to be shattered by the stock market crash in October of that year. Within a year, Knight saw much of his wealth wiped out and, in November 1930, he was forced to sell Spotswood Hall. “Regarded as one of the feature residential transactions of the season,” according to a contemporary newspaper account, the sale was reported to have garnered Knight $50,000. “It is understood that Dr. Knight plans to go to Florida for the winter.” The Knights did not return to Atlanta but lived in Safety Harbor, Florida, before moving to St. Simon’s Island, Georgia, in 1931. He died of heart failure in Clearwater in November 1933 and was buried at Christ Church at Frederica on St. Simon’s Island.

Walter Clay Hill Sr. (1880–1962)

The new owner of Spotswood Hall was Walter Clay Hill Sr., a vice-president of the Retail Credit Company, now Equifax. He was born in Monticello, a small town sixty miles southeast of Atlanta, the son of Hubert C. Hill and his wife Elizabeth Pope Hill. Hubert was a school teacher in the 1880s, but by the turn of the century he was working as an insurance agent. Walter graduated from the University of Georgia, where his uncle Walter B. Hill was chancellor, and by 1900 was also selling insurance in Monticello. [6]

Shortly, however, he moved to Atlanta and, in 1904, went to work for the Retail Credit Company. Founded in Atlanta in 1899, the company established offices in Dallas and Cincinnati in 1902 and was opening offices in Kansas City and Chicago when Hill joined the company. In 1905, an office was opened in San Francisco and two years later in New York and Philadelphia as well. Others followed and, in 1919, offices were opened in Montreal and Toronto, the first step in its growth to a position that is now global in scope. In the mid-twentieth century, it was one of the nation's largest credit-reporting agencies, but suffered from allegations of wrong-doing in the 1960s and 1970s, after Hill was dead. Renamed Equifax in 1976, it remains the oldest of the three big agencies.

The company prided itself on its ability to promote from within and, by the time the company was incorporated in 1913, Hill was a vice-president. His career with the company eventually made him president and chairman of the board and he remained a director of the company until his death.

He married in 1914, apparently for the first time, to Maryland-born Rebecca Travers (1886–1967). How they met and where they were married has not been documented, but in October 1917, their first child, Laura (1917–1995), was born in Atlanta. She was followed by Walter C. Hill Jr. (1919–1981) and Travers Hill (1925–2013). In the first years of their marriage, they rented a house on Peachtree Place, but sometime after 1920, they bought a house at 244 Peachtree Circle in fashionable Ansley Park

The Hills were members of the First Presbyterian Church as well as the Piedmont Driving Club and the Capital City Club, and he was also a member of the Commerce Club. He had begun a long tenure as a trustee of the Atlanta Art Association in 1928 and, later, would serve as vice-president, president and chairman of the board. The Walter C. Hill Auditorium at the Woodruff Arts Center is named in honor of his long support of the Association. He was also a member of the Atlanta Historical Society. Painting and jewelry-making were hobbies; his small painting of the house hung in the living room of Spotswood Hall in 2004.

By the time the Hills acquired Spotswood Hall in late 1930, the economy was plunging deeper into depression, and Hill may have had little time or inclination to contemplate remodeling his new home. Not until Roosevelt’s “Hundred Days” in the spring of 1933 was some measure of confidence in the economy and the nation restored. Perhaps Hill, too, felt more confident about the future and saw the advantage to be gained in the Depression’s cheap materials and cheaper labor.

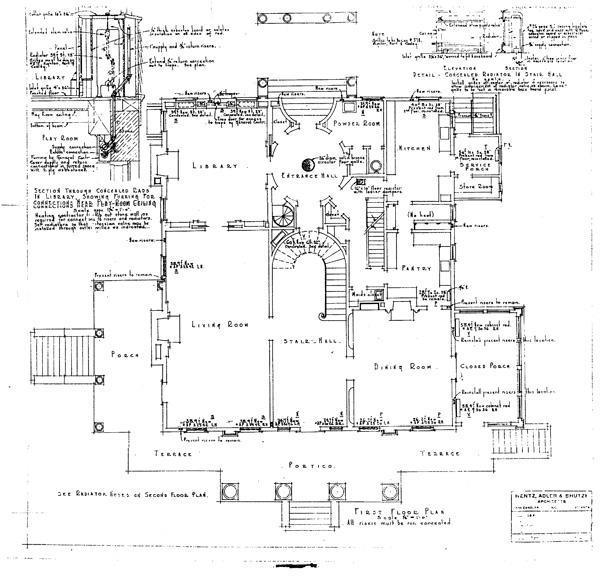

The house on Argonne was nearly twenty years old by then and, although the Neo-Classical exterior remained as handsome as ever, the house was not particularly large and the interior was, by then, somewhat less than fashionable. So, by the spring of 1933, Hill engaged the services of Atlanta’s premier architectural firm, Hentz, Adler & Shutze to enlarge the house and redesign its interior. [7] Philip Trammell Shutze (1890-1982) had firmly established his reputation in the 1920s with a variety of spectacular designs that culminated, perhaps, in Edward Inman’s magnificent Swan House in 1928. By 1933, the Depression had forced the firm’s partners to forego their salaries that year and the next and it is likely that the Hill commission was one of the firm’s most important jobs during the period. In the end, Shutze’s remodeling of the house, which was completed in 1934, ensured that Spotswood Hall would remain one of the city’s great architectural landmarks.

|

Figure 8. Shutze's plan of the first floor of Spotswood Hall with his proposed changes, most of which were executed. (Atlanta History Center) |

The Recent Past

The growth of Atlanta’s northwestern suburbs was slowed by the Depression and World War II, but by the time most of the area was annexed into the city in 1954, demand for building sites in northwest Atlanta had already increased dramatically. In the 1950s and 1960s, a number of the old estates and large lots were subdivided for construction of another generation of up-scale residential development. In 1952, Hill, too, began subdividing his 6.4-acre lot, selling two lots that year, a third in 1954, and a fourth in 1961. However, they appear to have made few changes to the house itself. Hill died in October 1962; his widow continued to occupy the house until her death in 1967. [8]

|

|

Figures 9–11. The dining room at Spotswood Hall, 1950, dressed for a promotional photo shoot for silversmiths Reed and Barton. (Owners' collection) |

In July 1968, Hill’s estate sold Spotswood Hall to John W. Callahan along with “all of the following items as presently installed in said house: (a) all air conditioning units, (b) linen press, (c) all wall-to-wall carpeting, (d) all venetian blinds and all curtains and drapes in said house.” At the same time, development of Arden at Argonne had begun on the northern part of Hill’s old estate, including the site of the estate’s garage, stable and servant’s house, all of which had been renovated by Shutze in the 1930s. By that time, too, the driveway from Argonne had been closed and entry was now via a driveway at the rear from Arden at Argonne. [9]

In February 1977, Callahan sold Spotswood Hall to Ian Robert Wilson, an executive with Coca-Cola. Wilson redesigned the old kitchen by removing the scullery and butler’s pantry and combining the spaces. A cabinet that may have come from one of these spaces is now located in the furnace room.

In 1982, the house was purchased by Frank Jameson Rees and his wife Ruth Andre Rees, who are thought to have installed the existing driveway from Argonne Drive, connecting it to the old driveway at the rear which still continued through to Arden at Argonne. They lived there until March of 1988 when they sold Spotswood Hall to Mr. and Mrs. Williarm R. Dawson III. It is unclear what changes, if any, they made to the house before the present owners, Eric and Susan Friberg, acquired the house in 1992, by which time it had been renumbered 555 Argonne Drive. Under their stewardship, the old rear driveway to Arden at Argonne was closed and a garage constructed in its place. [10]

![]()

Notes

1. Franklin Garrett, Atlanta and Environs, Vol. II, (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1954), 563–564, 575.

2. Fulton County Deed Book 356, 30.

3. Lucian Lamar Knight, "Shelby Smith," A Standard History of Georgia and Georgians, Vol. 4 (New York: The Lewis Publishing Company, 1917), 2196-2197. Inexplicably, Shelby Smith appears to have been enumerated twice in the 1910 Federal census, once as a divorced boarder on Mitchell Street near downtown Atlanta and again with Nell and their children at their home in Edgewood.

4. Fulton County Deed Book 381, 401-402; Plat Book 6, 46. The plat, dated December 8, 1913, is entitled “Property of Shelby Smith” and shows the house and garage but no other landscape features. Also see Peggy Reeves, “Spotswood Hall takes Marjorie Bell on a trip down memory lane,” Northside Neighbor, 1989. Marjorie Bell was Shelby Smith’s daughter. Shelby Smith is named on two plaques in the lobby of the Courthouse, one designating his service on the commission and the other his service on the building committee for the Courthouse.

5. Coleman & Gurr, “Lucian Lamar Knight,” Dictionary of Georgia Biography, Vol. II. Through his mother's family, whose roots were in Athens, Georgia, Knight was related to Henry Grady and the Lamars and the Cobbs, both of which were part of the South's antebellum aristocracy.

6. “Walter C. Hill Dies; Retail Credit President,” Atlanta Constitution, 19 October 1962.

7. Listed as Job #707, twenty-five sheets of drawings for this remodeling are included in the collection of the Atlanta History Center.

8. Fulton County Deed Books 2754, 507-508; 2949, 143; and 3683, 407; 4653, 315; 4825, 252-252; 4879, 470.

9. Fulton County Deed Book 1317, 476; Fulton County Deed Book 4933, 367; Plat Book 90, 47.

10. Fulton County Deed Book 15059, 45.

Select Bibliography

Architectural Plans

Hentz, Adler, & Shutze plans for additions and alterations to the house are at the Atlanta History Center (Job #707, 25 sheets). Plans allow reconstruction of the original floor plan of the house.

Biographical Sketches

“Lucian Lamar Knight,” Coleman & Gurr, Dictionary of Georgia Biography (University of Georgia Press, 1983).

Elizabeth Meredith Dowling, American Classicist: The Architecture of Philip Trammell Shutze (Rizzoli, 1989).

Directories

Atlanta City Directories, 1910-1921. Address first appears in 1914 directory (data collected fall of 1913); first numbered 505 Argonne; renumbered 555 Argonne in 1992.

County and Local History

Cooper, Walter G. Official History of Fulton County. Spartanburg, SC: The Reprint Publishers, 1978 reprint of 1934 edition.

Garrett, Franklin M. Atlanta and Environs: A Chronicle of its People and Events. 2 vols. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1969 reprint of 1954 edition.

Garrett, Franklin. “Necrology.” Unpublished MSS at Atlanta History Center.

Knight, Lucian Lamar. A Standard History of Georgia and Georgians. Vol. 4. New York: The Lewis Publishing Company, 1917. Contains biography of Shelby Smith, pp. 2196-2197.

County Records at Courthouse

Fulton County, GA. Records of Deeds, Mortgages, and Plats provide chain of title and prove house’s existence in 1913.

Fulton County Deed Book 15059, p. 45.

Fulton County Plat Book 90, p. 47.

Oral Interviews

The daughter of Shelby Smith was interviewed by the Northside Neighbor in 1989 (see below). Smith’s grand-daughter also provided biographical information to the compiler of this nomination. The Fribergs provided notes from interviews with the daughter of Walter C. Hill, Sr.

Historic Maps and Plats

1913 plat, Fulton County Plat Book 6, p. 46. Shows roads, property boundaries, footprint of house and of servant’s house, but no internal drives or walks.

1927 U. S. G. S. Map. Shows relatively isolated location of house. Modern road system was in place but development was limited west of Habersham.

1968 plat, Fulton County Plat Book 90, p. 47. Shows Argonne Drive, boundaries of 2.07 acre tract, footprint of house, and shaded outline of part of Shutze’s 1933 rear driveway pattern.

Newspapers and Magazines

“Spottswood [sic] Hall Home of Georgia Historian, Is Sold,” Atlanta Constitution, 1930. Recounts sale of house but does not offer any explanation for Knight’s move to Florida.

“Walter C. Hill, Sr. Dies; Retail Credit President,” Atlanta Constitution, 19 October 1962. Lengthy obituary.

“‘Spotswood Hall’ takes Marjorie Bell on a trip down memory lane,” Northside Neighbor, 1989. Marjorie Bell was the original owner’s daughter and lived in the house as a child.

“Sitting Room Kitchens,” Kitchen and Bath,, July 1990, pp. 28-31. Shows kitchen remodeling of 1989 but offers little information on the building’s evolution.

Norris Broyles, “‘Atlanta’s Monticello’ Graces Argonne Drive,” Atlanta 30305, January 1997. Some inaccuracies.

Historic Photographs

“Spotswood Hall,” c. 1925, Atlanta History Center photograph #3890.

“Spotswood Hall”, c. 1929, photographed prior to Shutze remodeling and featured in Annie Hornady Howard, Georgia Homes and Landmarks (1929), pp. 136-137.

Three interior photographs, c. 1950. Reprints of photographs and press release, acquired from Hill descendants by current owner. Taken for Reed & Barton promotion that was photographed at Spotswood Hall.

Exterior photograph, c. 1950. Reprint of photograph acquired from Hill descendants by current owner.

Other

“A. Ten Eyck Brown, A. I. A.,” architectural catalog, 1924. Copy in Brown file at Historic Preservation Division, Georgia DNR. Does not include Spotswood Hall.

Federal Census, 1850-1930, provided personal details on several of the people associated with the house.

![]()

|