Located on the south side of Lanier Avenue (S. R. 54) just west of the courthouse square in Fayetteville, the Holliday-Dorsey-Fife House is an excellent example of the Greek Revival style as expressed through a vernacular building tradition. Few houses of this sort were built in this part of the upper Piedmont and, with the Courthouse and Starr's Mill, it is one of the defining landmarks of Fayette County. The house is not "high style," something of which there was very little in the western Georgia piedmont anyway. Rather, the house represents a vernacular interpretation of the Greek Revival that was probably worked out between Holliday and the carpenter in charge of enlarging and remodeling an older house. Architects were virtually non-existent in antebellum Georgia and most building design and construction followed a long vernacular building tradition that stretched back hundreds of years. In the years before the Civil War, design and details were either copied outright from some of the widely circulated pattern books of the period or, drawing from vernacular tradition, made up on the spot to meeting existing conditions.

Part of that vernacular tradition included conservation of materials and adaptation of old buildings so that, as a result, very few antebellum buildings, particularly outside the wealthier cities and towns (which Fayetteville was not), were built to a single design at a certain point in time. Instead, what we see today as Greek Revival is, in reality, often the remodeling of an older plain-style or, in the eastern part of the state, Federal house. Although the style became fashionable in the 1830s, it's popularity had not waned in the 1850s, when Italianate elements like those on the Holliday house begin to appear on otherwise Greek Revival designs. By that time, too, settlement of Fayette and Henry counties had proceeded to the point that there was wealth enough for a few to attempt monumental residential building.

Most of the images will embiggen should they be clicked upon. Unless otherwise noted all photographs were taken by the author in 1996. |

|

Figure 3. View of Mossy Hill in Wilcox County, Georgia, a classic example of the plantation-plain style. John Holliday's original house may have looked something like this, but with chimneys in the rear rather than on the ends.

Figure 4. View of west side of the home of the Hollidays' neighbor William Bennett. The differences in windows and floor levels apparent between the front and rear of the house suggests an evolutionary history with some parallels with the Holliday-Dorsey-Fife House. The present Bennett house is the result of a large addition to the front of an older and much smaller house. (2012)

Figure 5. View of west side of Holliday-Dorsey-Fife House, where the fenestration provides a clue to the building's evolution. Whereas the Bennett house was enlarged by a new addition to the front of the original house, Holliday enlarged his house by an addition at the rear.

Figure 6. View of Dorsey-Talmadge House at Lovejoy, originally built in the 1830s and remodeled in the Greek-Revival style in the 1850s

Figure 7. View of Johnson-Blalock House in Jonesboro, remodeled in the Greek Revival style in the 1850s by James and Martha Holliday Johnson. |

Plantation Plain Style

The architecture of the house that John Stiles Holliday occupied in 1846 is commonly called "plantation plain style," a term coined by architectural historian Frederick Doveton Nichols (1911-1995). It is not really a style at all, but rather a regional variation on the so-called I house, both describing a type of house, either wood-framed or log, sided with clapboard, two stories (sometimes a story and a half) high and one room deep.In addition, the plantation plain style variation found all across the south included a one-story porch spanning the front of the house, usually wiith a simple shed rather than hipped, which was much harder to frame and finish. Usually, too, there was a one-story, shed-roofed range of rooms and/or porch across the rear of the house. These were perhaps the most common Southern houses before the Civil War and continued to be built occasionally through the remainder of the nineteenth century. Many had rooms added to the porches at an early date, and stylistic details like Greek columns or sawn Eastlake spandrels and brackets were often used to update older plain-style residences. Numerous examples of this vernacular building tradition survive, although often buried beneath later remodelings and additions.

The earliest of these houses were typically built to a traditional hall-and-parlor plan, but as the nineteenth century wore on, plain-style houses came to be built with more equally-sized rooms and a center hall. That the original portion of the Holliday-Dorsey-Fife House was built on a center-hall plan is perhaps the best indication that the house was built around the time that Dr. Holliday acquired the property in 1846.

Two of the area's most important local landmarks bear comparison with the Holliday-Dorsey-Fife house, both stylistically and in the manner in which they were created: both were Greek Revival remodelings of older, plantation plain-style houses. The Crawford-Talmadge house at Lovejoy is perhaps the best-known example. Originally built in 1835 by Solomon Dorsey's sister Althea and her husband Thomas Crawford, the house was more than doubled in size in the 1850s, perhaps in 1858, and remodeled in the fashion of the Greek Revival by the addition of six Doric columns across the front. In 1859, John Stiles Holliday's sister Martha and her husband, Col. James F. Johnson, probably used the same builder as the Crawfords, to remodel their new house in Jonesboro. It had been built originally in the 1840s and, as her brother had done in Fayetteville, the Johnsons remodeled an older house by adding eight massive two-story Doric columns in the front.

Not so similar stylistically since it lacked the monumental Doric columns, but quite similar in its evolution, was the Crawford-Dorsey house in Lovejoy, now lost. Built by William Crawford, Althea Dorsey Crawford's father-in-law, in the 1820s, the house was bought by her brother Stephen Green Dorsey and expanded and remodeled in the 1850s. The old William Bennett house in Fayetteville, facing Stonewall just west of the Holliday-Dorsey-Fife house site, was also an earlier house, built in the 1820s or '30s, that was doubled in size, probably in the third quarter of the nineteenth century, but without the Greek Revival remodeling.

The Holliday House (1846-1871)

Most likely, Dr. Holliday built a new plantation-plain-style house after he acquired the property in 1846, although evidence for the typical one-story, full-width porch and the shed-roofed range of rooms across the rear is only circumstantial. Several peculiarities of construction method and materials are useful in distinguishing the original structure from Holliday's Greek-Revival house. The original house was a braced-frame structure, two stories high but only one room deep, with two rooms flanking a central hall on both floors.

The original portion of the Holliday-Dorsey-Fife House was unusual in having its chimneys on the rear and not on gable ends, as was more typical in the period. The one-story Stone-Holliday House on S. Glynn Street appears to have originally had two rooms on either side of a central hall with fireplaces on the back (west) side of the building. Likewise, the Jonesboro house of Holliday's sister Martha and her husband has rear chimneys. Perhaps this was a local variation of standard chimney placement and, if so, a significant example of the virtually limitless combination of elements that vernacular architecture is capable of producing.

|

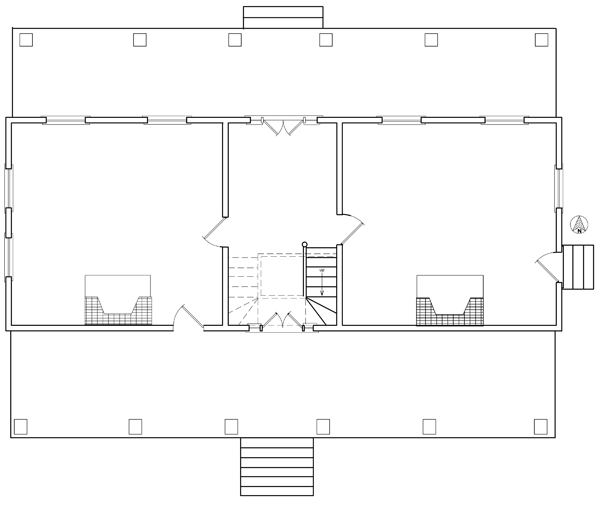

Figure 8. Probable floor plan of the Holliday House when it was originally constructed in the 1840s. Fenestraiion across the rear (south) side of the house as well as the location and configuration of the stairs to the second floor and the precise dimensions of the porches are hypothetical. (Drawing by auhor, 2012) |

Enlargement of the house would have been almost as significant an undertaking for Holliday as building from the ground up. The entire roof structure, the front porch, and probably the rear porch as well would have been removed, and an entirely new roof structure was built to engage the enlarged house and its new front porch. Both east and west sides were completely resided in order to disguise the joining of the old structure with the new, but the original flush siding at the first floor level on the front of the house was retained and new flush siding added to replace the earlier lap siding at the second-floor level. The awkward joining of the flush siding from different eras is still evident on the house today.

The clearest mark of the expansion of the house is the line of partially staggered butt joints in the floor boards in the halls on both floors. These are most visible in the closet under the stairs, which marks the location of the rear wall of the original house. Although the original south walls of both upstairs and downstairs halls were removed in 1855, all evidence of the wall in those locations could not be eliminated. In particular, the posts that framed the original rear door opening intruded into the line of the hall walls. With restructuring, the posts could be narrowed but to have removed them entirely would have necessitated rebuilding much of the original rear wall of the house. In addition, because the flooring of the original house was retained and was nailed to the sills at that location, it was easier to simply cut the reduction in the post width flush with the then-existing floor boards. Finally, the timber that formed the original top plate of the house was also left in place, since it carried part of the load of the new roof, and its passage across the second floor hall bisects the ceiling of that space.

The double doors, sidelight, and transom at the rear of the original first-floor hall were simply relocated to the new rear wall of the hall. The corresponding double doors, sidelights, and transom that formed the front entry to the original house were relocated to the second floor where they open on to the balcony that was also added in the 1850s. New double doors, sidelight, and transom matching the original were installed on the main floor. Throughout the house, the few modern window sash are easily distinguished from the nineteenth-century window sash, and close examination shows that the nineteenth-century sash fall into two main groups. Thinner muntins, approximately ½" thick, with blown glass are found in ten of the windows, including all of those on the front and one each on each end. These probably represent most of the windows in the original house, some of which would have been relocated in 1855. The 1855 sash are very similar to the older sash but have ¾" muntins and glass that, though imperfect, was probably machine rolled. Differences in shutter hardware have also been noted, corresponding to the two different types of sash. Inventory of the shutters themselves, now in storage in the crawl space, will probably show two different eras there as well.

Slight differences between the front and older part of the house and the newer rooms to the rear can also been noted in the care with which the flooring was laid on the first floor. At the front, each floor board was carefully chiseled as necessary to level the finished flooring against the uneven tops of the rough-sawn floor joists. Although this was done with the flooring in the rear of the house, it was not done with the same consistency as that at the front, an indication of the movement toward more standard dimensioning of lumber from the saw mill and, thus, joists that were more "true" and straight.

Other differences between the two parts of the building can be noted in profiles of muntins in the window sash and of the window and door casing. Differences in the dimensioning of framing material are also evident, but the combination of sawn joists, rafters, and studs with hewn sills and corner posts that is found throughout the house is typical of the 1840s and 1850s.

Notes on a kitchen: It is not at all clear where the Hollidays' kitchen was located, but it was almost certainly located in a building seperate from the main house. The heat and high risk of fires from open-hearth cooking, the use of slaves, and the early nineteenth century distaste for smells of cooking in the house combined to keep most cooking in a separate cook house, at least for those who could afford that luxury. After the Civil War, as the use of cast-iron cook stoves greatly reduced the risk of fire and the loss of slaves made kitchen service from a separate building increasingly untenable, the detached kitchen became a thing of the past. Although no documentation has been found for a separate kitchen building, it seems likely that one was located on the property in the 1850s.

The Holliday-Dorsey House (1871-1903)

The present building suggests that Solomon Dorsey made few, if any, changes to the Holliday House after he bought the property in 1871. The house was still relatively new and provided ample room for his wife, six children, and his widowered brother-in-law Frederic Glass. Perhaps somewhat neglected after the Hollidays moved out during the war, the house might have required some repairs and considerable redecoration, but there is no reason to believe that the Dorseys delayed in bringing the house into good order. In most ways, the Dorseys' use and enjoyment of the house for the remainder of the nineteenth century was probably little different from that of the Hollidays.

One change that the Dorseys may have made was to bring the kitchen inside or attached to the main house. but that is not at all certain. Still, with cast-iron stoves in widespread use, there was less danger of fire, and fewer and fewer people continued to maintain a separate kitchen building. Utilizing an existing door from the back porch to the dining room, the new kitchen would have greatly simplified serving meals, especially when one no longer had slaves to service the table. Beyond that, the exterior and, to a lesser degree, the interior would have been repainted occasionally or generally redecorated, and the wood-shingled roofing replaced once or twice in the nineteenth century.

The Holliday-Dorsey-Fife House (1903-1968)

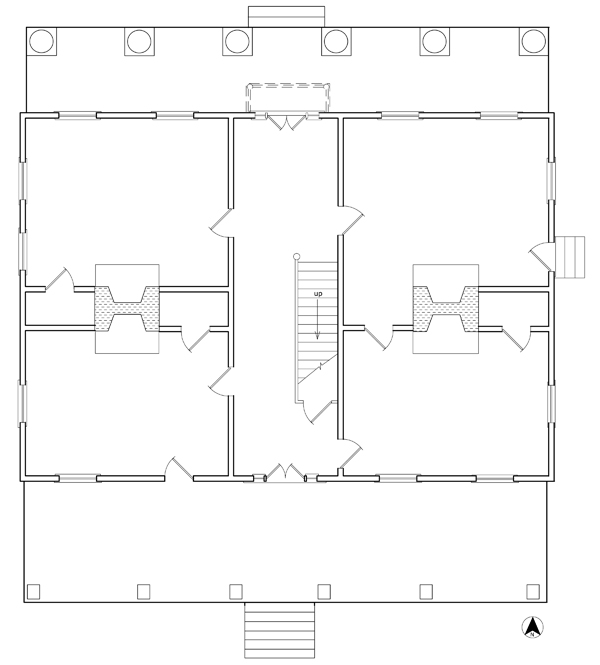

The Sanborn Fire Insurance Company map of Fayetteville from 1925 provides some of the earliest documentation for the house in the historical record. Although the map does not note any outbuilidngs on the property, it does document the existing footprint of the house, including a one-story porch across the rear of the house rather than the shed-roofed range of rooms present today.

The 1925 map also indicates that the main block of the house was roofed in metal, most likely using standing-seam metal roofing. The roof-covering on the back porch is not noted, but it may have been metal as well. Metal roofing could have been installed when the house was constructed in the 1840s, but that would have been very unusual for the area. Metal roofing could also have been used when the house was enlarged and remodeled in the 1850s, but machine-sawn, wooden shingles would have been more typical for that period in the western Georgia piedmont. The loss of all of the historic roof decking on the main block of the house adds to the difficulty of dating the metal roofing. Exactly when and by whom it was installed remains to be documented.

Electrical service from Senoia to Fayetteville was established in 1928, but the Fifes were apparently not early adopters of that not-so-new technology. The Fifes continued to use an outhouse as well, as did many others in that period. Except for the increasing presence of automobiles, Fayetteville remained in many ways a nineteenth-century town.

Following Mrs. Fife's death in 1938, the house was thoroughly renovated. Cecil Fife took out a loan for $36,000 in 1939 for the stated purpose of adding plumbing, electricity, and heating to the house. Bathrooms were added in the southwest room on each floor, which were almost certainly the first indoor facilities the house had ever had. The original door openings from the hall into the southwest rooms on each floor were relocated and replaced as well.

The kitchen may have been located in the southwest room on the first floor, since there is no evidence for a kitchen in any of the other rooms of the house. To accommodate the new bathroom, the kitchen was reconfigured, but the cabinets and countertops present in 1996 were most likely installed in the 1950s.

It may have been at this time that a door was cut between the kitchen and the front parlor, which was probably used as a dining room after 1940. Lighting and convenience outlets were also added throughout the house. At least one of the existing light fixtures appears to date to the early twentieth century rather than to the 1940s, which suggests that electricity may have been installed prior to the renovation just before World War II.

The entire back porch was completely or mostly rebuilt at this time, although the more recent alterations to this addition have obliterated much evidence for those changes. The sills, roof rafters, and roof decking were the only historic materials left on this addition in the 1990s, but it may occupy the footprint of the original back porch. Finally, it was probably at this time that the metal roofing was replaced with asphalt shingles.

![]()

Physical Description

The house as it existed in 1996 had been little altered since Fife's renovation in 1939. The transition to commercial use, however, began a slow decay of its physical condition, mostly the result of deferred maintenance, especially after the 1970s. In spite of that, the house retained most of its historic floor plan, except for the remainder of the back porch, which was enclosed and the floor framing and foundation replaced in the last quarter of the twentieth century. On the remainder of the house, nearly all of the original, nineteenth-century windows, doors, mantels, and millwork remained intact. The description here describes the house as it existed at that time.

|

Figure 13. View west of Holliday-Dorsey-Fife House.

Figure 14. View southeast of Holliday-Dorsey-Fife House.

Figure 15. View northwest of Holliday-Dorsey-Fife House.

Figure 16. View northeast of Holliday-Dorsey-Fife House. |

A two-story building facing north, the house is end-gabled, with two center chimneys rising just behind the roof ridge. The building has five bays front and rear and three bays on each side. The house features a full-width, two-story front porch engaged under the main roof and a one-story, shed-roofed addition across the rear. The front porch is supported by six, fluted, Doric columns, and there is a small cantilevered balcony at the second floor above the main entrance. Typical for the period, simplified Italianate brackets, sawn out of 1" stock, are set at approximately 48-inch intervals under the eaves and under the gable returns on each end of the house.

Foundation

The house is set on brick piers that have been underpinned with brick and reinforced with modern concrete block at several locations. Several generations of masonory are apparent. In particular, the two chimney bases have both had significant additions to them, probably including complete rebuilding of the hearths.

One aspect of the building's evolution that has not been accounted for is the placement of the chimneys. Chimneys were almost always placed at the ends or sides of the house or, if the plan were two rooms deep, on the inside between the two rooms. Rear chimneys on an I-house are not typical in Georgia, but the Stone-Holliday House on S. Glynn Street has the same configuration. In that house, the rear chimneys are on what appears to have been originally a simple one-story, two room and central hall house.

The front porch foundation and the plinths for the columns are of poured concrete, the form marks clearly visible on the plinths. These foundations could have been part of the original construction in the 1850s, but they are most likely evidence for a twentieth-century reconstruction of the porch floor. A date that appeared to be inscribed on the top of this foundation was visible through deteriorated floor boards, but could not be deciphered in 1996.

Structure

|

Figure 17. View of t ypical post, brace, and joist connections to the sill.

Figure 18. View of north side of the northwest bedroom on the second floor, showing typical wall framing in the original portion of the house.

Figure 19. View west in attic, with the rear chimneys of the original house visible to the left. |

Before the Civil War, braced, timber-frame structures with mortise-and-tenon joinery were typical of the best-built houses. Not until the 1850s did that begin to give way to the lighter "balloon" frame that evolved in the two or three decades before the war. The balloon frame, which depended on mass-produced cut nails and lumber machine-sawn to standard dimensions, could be erected far more easily than the timber frame. With improvements in nails, the balloon frame became the norm for nearly all residential construction after the Civil War.

The main, two-story block of the Holliday-Dorsey-Fife house, which appears to be constructed entirely of Southern yellow pine, uses a braced-frame with traditional mortise-and-tenon joinery, using hewn sills and posts and machine-sawn, dimensional lumber for joists, studs, rafters, and other framing members. The house has hewn sills, approximately 12" square, except where they have been replaced across the rear of the main block of the house and along the west end of the front. The two-story main block of the house also has hewn corner posts mortised into the sills, with large cross braces mortised and pegged to the sill as well. These posts also identify the corners of the original house that Holliday remodeled in the mid-1850s.

The sills of the rear, shed-roofed addition, which is probably a replacement of an original structure in the same location, are all sawn lumber, unlike the hewn sills of the main house. The east end of this addition was originally an open porch, enclosed since 1970 at which time all the floor joists and flooring were completely replaced. The structure's original roof rafters, with their exposed ends, and the painted underside of the roof decking are visible above the ceiling of the room at the west end.

|

Figure 20. View of front (north) side of Holliday-Dorsey-Fife House. |

Fenestration

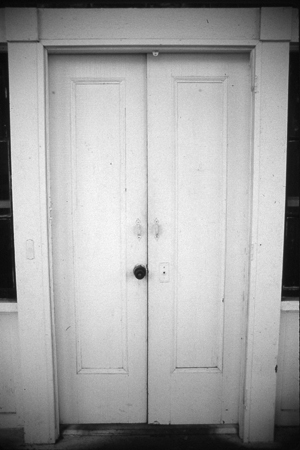

Double-door entries at front and rear of the first floor have nearly identical sidelights and transoms, all fixed and glazed with clear glass, some of which is original. The door opening is about 3'-7" x 6'-10", each door with a single vertical panel. Both of these entries were probably part of the 1855 construction, with the original front entry moved to the upstairs.

The same configuration of double doors, sidelights, and transom appears at the second floor above the main entrance but is slightly different in detail from the other two, later entries. The single door opening from 103 on the east side of the house appears to be original to the 1855 remodeling of the house or at least of nineteenth century origin, although the door itself is certainly twentieth century in origin. This door opening was created in what had been a window opening in the original 1840s house.

The windows in the house are double-hung, with six-over-six sash at the second floor and six-over-nine at the first floor. Second floor windows are approximately 3'-6" x 6'-0"; the lower windows are approximately 3'-5" x 7'-2". Window sills are all just under 3" thick and all have been covered with sheet metal. There is a single opening around 1'-8" x 2'-0" centered in each gable. The one at the east end was hung with a pair of louvered shuuters, while the opening at the west end was closed by a sheet of plywood nailed across the inside of the opening. The sash from these windows are in storage in the attic.

As mentioned earlier, two generations of antebellum sash have been noted in the house. The oldest, which relate to the original house that Holliday remodeled, have ½"-thick muntins with the stiles and rails cut from 1-3/8" stock and are found at all of the windows on the north facade as well as at the east windows in 208. The other window sash have ¾"-thick muntins with stiles and rails out of 1-5/8" stock and date to Holliday's remodeling of the house in the 1850s. The glass, too, in these windows differs, with that in the older windows having the pronounced irregularities associated with an earlier glass and the later glass exhibiting more of the characteristics of modern, machine-rolled glass.

Figure 21. View of front entrance.

Figure 22. View of front doors, which probably date to the 1840s. (Photo by author, November 1996)

Figure 23. View of six-over-nine windows at the west end of the house, typical of the first-floor windows in the original house. (Photo by author, November 1996) |

All of the windows originally had exterior louvered shutters, some of which are in place in the front, although hung upside down. The remainder are stacked in the crawl space of the house and suffering some deterioration. As with the windows, two kinds of shutter hardware can be identified on the house. At the earlier, thin-muntined windows, a traditional "elbow" hinge was used; at the later windows a different, self-locking style of "butterfly" shutter hinge was used.

The placement of the window openings on the east and west sides of the house relates to the two phases of building construction, with the single window on each side of the house which light the newer, rear rooms contrasting with the two windows per room in the older, front part of the house. Aside from the door on the east side, which probably replaced a window opening in the original house and was created to provide Holliday with an outside entrance to his office, the remaining window does not line up with the corresponding window on the west wall of the parlor. The same misalignment occurs in the front rooms on the second floor, with the windows on the west side more evenly spaced than those on the east.

Exterior Finishes

Lapped wood siding, nominally 1" by 7", is laid up with cut nails and a 5-6" reveal and covers the east, south, and west sides of the main body of the house. Painted white, all of it probably dates to the 1855 remodeling. The flush siding with rabbetted edges used on the north or front facade dates to the antebellum period. The lower part is sided in boards approximately 8" in width; at the second floor and on the porch ceiling the width of the boards is approximately 11", with a narrower 4" board seperating the two sections. The lower siding dates to the original house and its one-story porch. When the porch was raised in 1855, the wider siding was used to complete the flush siding of the front, an excellent example of the traditional frugality with building materials, even at the expense of a perfectly uniform appearance.

Window and door openings are trimmed with six-inch casing, backband, and drip cap. The front door is further detailed with corner blocks above the door and a raised and inverted pyramidal panel at the top of the architrave. Panels beneath the side lights are plain and unmolded. The balcony is cantilevered from the second floor with no supporting brackets. It is surrounded by a simple balustrade of square pickets and rounded newels, much like the balustrade in the hall. The porch ceiling and the underside of the balcony are both finished with boards 10-12" wide.

The existing porch flooring is in fairly good condition except between the two center columns where the floor has been repaired. In this area, an undeciphered inscription is partially visible on the top of the concrete foundation. The tongue-and-groove floor boards measure 1⅛" thick and 2¼" wide, dimensions typical of nineteenth century material.

Interior

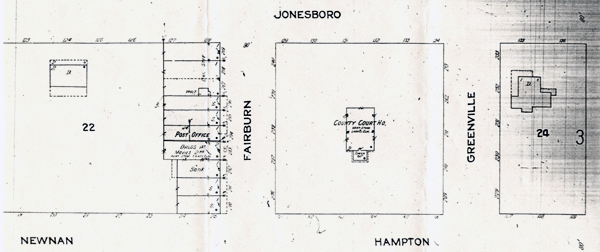

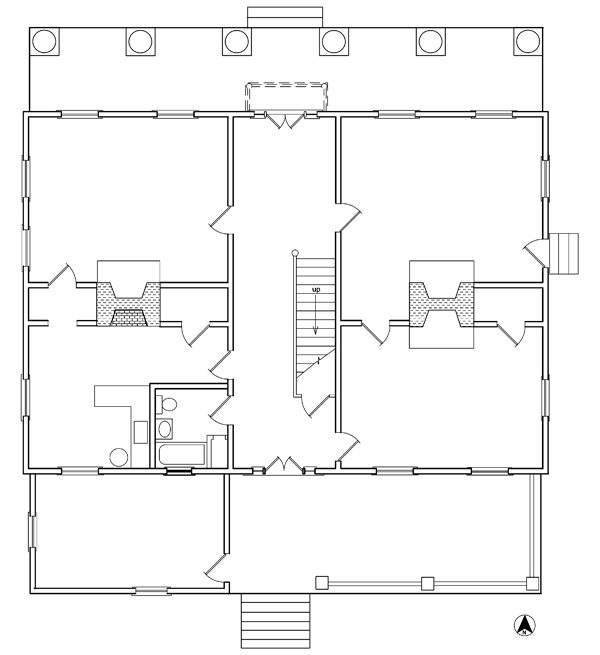

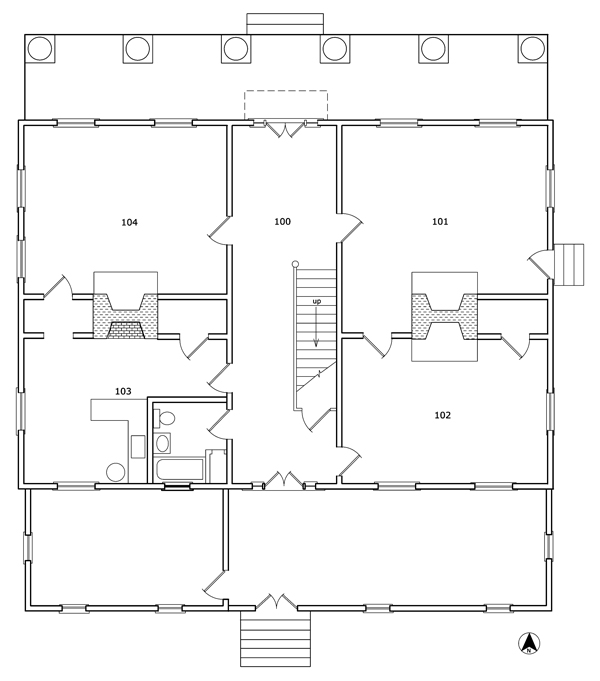

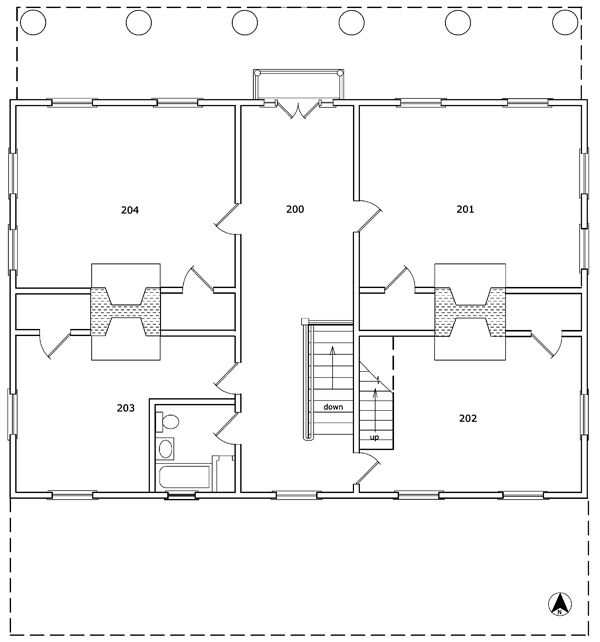

The house has a classic Georgian floor plan, each floor with two rooms on each side of a center hall. The rooms are relatively small: about 15' x 19' for each of the older rooms at the front and 13' x 19' in the rear). Ceilings are relatively low for the period, because the original ceiling height was maintained when the new rooms were added in the 1850s. At the William Bennett house, as well as the Crawford-Talmadge house, higher ceilings were constructed on additions with the difference in ceiling heights between old and new addition simply ignored and accommodated by one or two steps between the different sections. In addition, Holliday made the new rooms smaller than the old, when it might have been expected that the new rooms would have matched the dimensions of the old. These are among the oddities of all vernacular architecture.

In 1940, the plan of the two rooms in the southwest corner of the house was altered by the insertion of identical bathrooms on both floors. At that time as well, the small closet connection between 102 and 104. Aside from these changes and the previously at 103, which probably only opened into 104, was turned into a butler's pantry and discussed alterations to the back porch, the plan of the house remains essentially as it was created in the 1850s.

|

Figure 24. Plan of first floor of Holliday-Dorsey-Fife House as it existed in 1996. (T. Jones, 1996)

Figure 25. Plan of second floor of Holliday-Dorsey-Fife House as it existed in 1996. (T. Jones, 1996) |

Flooring

|

Figure 26. View of typical 19th-century flooring. |

All of the floors in the house were originally tongue-and-groove, 1"-thick stock, face nailed, and averaging about six inches wide, with the original flooring in the rear rooms slightly narrower than the flooring in the front rooms. Much of the wood is heart pine, the reddish center or "heart" from old-growth trees. The wood used was not of the very best grade, as evidenced by the number of knots. Nearly all of the flooring is still intact although that in the southeast room on the first floor is badly worn and at least part of the flooring in both bathrooms was replaced by plywood decking. The original flooring in the remainder of the southwest room is still intact but was overlaid, probably in 1940 but perhaps earlier, with a narrower tongue-and-groove pine flooring. Since 1970, the floors have been sanded and refinished, probably not for the first time. In some places nearly half an inch has been removed from the original thickness of the boards, leaving little room for further sanding.

Ceilings

All of the rooms in the house originally had board ceilings, much like those still visible on the ceiling of the front porch. Nearly all of them have been covered with sheetrock in recent years but they remain intact and are still visible in the closets and in the spaces above the lowered bathroom ceilings. At least one of these ceilings, in the small closet off the northeast corner of the 1939 kitchen (Room 103), has never been painted.

Walls

Walls throughout the house are plastered, with the oldest plaster on split lath, the newer plaster on sawn lath, an illustration of the transition to machine-sawn lumber that would soon be complete. The northwest room on the second floor has been completely gutted of plaster and the southeast room partially gutted. The plaster in the remaining rooms is in very good condition, except in the southeast room on the first floor where alterations for commercial use appear to have been most extensive and in the southwest room where the bathroom installation resulted in the loss of most of the historic plaster in that corner of the room. All of the plaster has been extensively repaired in recent years, repairs that included installation of a skim coat that buried historic finish layers as much as an eighth inch or more beneath the present finished wall surface. This skim coat also reduced the reveal of the trim, particularly at the tops of the baseboards.

|

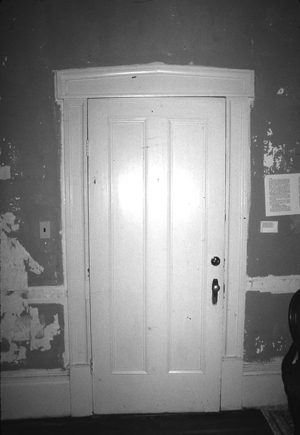

Figure 27. View of door between parlor and hall, typical of the earliest doors in the house. The header casing seen here was not used elsewhere in the house.

Figure 28. View of six-over-nine window typical of the original windows on the first floor of the house.

Figure 29. View of six-over-six window at the east end of the house, typical of second-floor windows in the original house..

Figure 30. View of typical original beaded baseboard.

Figure 30. View early wrought-iron latch on door between the two east rooms on the first floor. |

Doors

In addition to the exterior doors discussed above, there are several generations of interior doors. The earliest doors have two vertical panels and all of that type appear to date to the antebellum period. There are minor variations among the two-panel doors, but it is not clear which might be original and which might date to the 1850s. All of them appear to have been hand made with plane marks clearly evident, particularly on the reverse or inside of the panels. There is also a significant variation in the depth to which the reverse of the panels has been beveled, a common characteristic of individually-made doors.

Trim

The wooden trim in the house varies considerably from room to room and floor to floor, even where there was the apparent intent to maintain the same configuration. The trim in the 1855 parlor at the northwest corner of the first floor is unique in the house, featuring a wider, more detailed baseboard and pedimented architraves rising from the floor with molded panels beneath the windows. Only in southeast room are there panels under the windows and there they are unmolded.

The door casing in the center hall and that in the northeast room are quite similar and include a backband and molded stop. The exception is the doorway from the hall into the northwest room, which has more elaborate molding that is unique in the house. Paint analysis and more careful study of molding profiles could clarify details of the building's evolution.

Casing for the remainder of the doors and windows in the house is generally six inches wide, with slightly narrower stock at closet doors. All casing is finished with a back band in a simple, angled profile.

There were no crown moldings in the house until installation of the sheetrock ceilings. In the front hall the crown molding was applied in such a way that, from the stairs, one can look behind it and note an earlier wallpaper applied flush with the board ceiling. In the northeast bedroom on the second floor, there is a bed molding applied as a crown molding which probably dates to the early twentieth century.

Each of the mantles is unique and features variations on the popular design motifs of the period, including Greek and Egyptian revival styles. There is the likelihood that some or all of these were marbleized in the 1850s in imitation of the black marble mantles that were popular before the Civil War.

Paint and Wallpaper

A variety of historic wallpapers has also been noted in the house, spanning at least a hundred years of the building's history. Wallpaper probably played a highly significant role in the decoration of the house by the Hollidays, the Dorseys, and, certainly, the Fifes.

In addition to wallpaper, there is the strong possibility of grained finishes, particularly on the doors, and marbleized finishes, most likely on the mantels and baseboards. It appears that the woodwork has never been stripped and a full record of the paint chronology should be found for all elements of the house's trim, both inside and out. Even in the southeast room on the second floor that has been gutted, there are probably enough clues surviving in the remnants of plaster, paint and, possibly, wallpaper fragments that can still be located, if there is no further removal of material from the room.

Hardware

Only two antebellum lock sets, both surface-mounted rim locks, remain in place in the house. One set is at the double balcony doors at the north end of the second floor hall, where the sliding latches, lock and mineral knobs remain in place. The other is the lock with porcelain knob that survives on the closet door in the southeast room on the first floor. Typical of the period, all of the door knobs on the first floor would have been white porcelain while all of those on the second floor would have been brown, fired-and-glazed, mineral-clay knobs. The rest of the nineteenth-century door hardware was apparently replaced with Art Deco escutcheons and faceted, cast-glass knobs typical of the 1930s.

The wrought-iron thumb latch on the door between the two east rooms on the first floor is unique in the house. This simple latch might mark the door as one of the original doors in the house that was left in place when the house was remodeledd in the 1850s.

Other historic hardware includes the window sash locks, which were originally located only on the old first-floor windows; most are still in place. Also of note is the cover plate to a late nineteenth century mechanical doorbell on the front door.

Light Fixtures

The house was not wired for electricity until the twentieth century and probably not until after 1928. Since there is no evidence of earlier gas lighting in the house, oil or kerosene lamps would have been used prior to the installation of electric lighting. There are several historic light fixtures in the house, including the matched set for the two front rooms and the hall on the first floor (the fixture for the northeast room on the first floor is in the attic). In addition, the front porch light, which hangs from the underside of the balcony is an outstanding early light fixture as is the one in southwest room on the second floor. Both of these have holophane-like shades that were designed to more evenly disperse the light of the lower wattage bulbs of the early twentieth century. The fixture in the northeast room on the second floor probably dates to the 1920s or before, but may have been brought into the house from elsewhere. It still retains its inverted milk-glass shades.

|

Figure 31. View north of first-floor hall. |

Figure 32. View south of first-floor hall. |

|

Figure 33. View southeast in northeast room on the first floor. |

Figure 34. View west in northeast room on the first floor. |

|

Figure 35. View southwest in southeast room on first floor. |

Figure 36. View northeast in southeast room on first floor. |

|

Figure 37. View of mantlepiece at fireplace in southeast room on first floor. |

Figure 38. View southeast in southwest room on first fllor. |

|

Figure 39. View south in northwest room on first floor. |

Figure 40. View northeast in northwest room on first floor. |

|

Figure 41. View north in second-floor hall. |

Figure 42. View south in second-floor hall. |

|

Figure 43. View southwest in northeast room on second floor. |

Figure 44. View of mantlepiece at fireplace in northeast room on second floor. |

|

Figure 45. View northeast in southeast room on second floor. |

Figure 46. View northwest in southeast room on second floor. |

|

Figure 47. View of mantlepiece at fireplace in southeast room on second floor. |

Figure 48. View northeast in southwest room on second floor. |

|

Figure 49. View southeast in northwest room on second floor. |

Figure 50. View north in northwest room on second floor. |

![]()

1.History of Clayton County, p. 22.

2. See John Linley, The Georgia Catalog: A Guide to the Architecture of the State (University of Georgia Press, 1982), 22.

3. See Henry Glassie, Patterns in the Material Folk Culture of the Eastern United States, pp. 49-54, 109-112, for a discussion of Georgian design and planning.

![]()